Is there a more put-upon human being in the entire saga of humanity than Job? And is there a more troubling indictment and challenge to all notions of God that rest on his kindness, caring spirit and insistence on justice for his subjects?

The Book of Job is right about in the middle of the Old Testament, befitting its central role, its flashpoint status, as an inquiry into faith, justice, human perseverance, the nature of God, and the existence of evil.

It stands as the original investigation into “why bad things happen to good people,” and to read just a portion of the millions of words written about it in the (estimated) 2,500 or so years since its appearance is to understand that in detective terms, the investigation remains very much open and subject to a staggering array of analyses.

Here’s mine.

***

History is replete with epic struggles for supremacy, but few can compare with what God’s “good servant” Job faces: being set upon with utter ferocity by none other than Satan, who is working in cahoots with his traditional nemesis God, the Omnipotent Creator of the Universe. See those two coming around a corner huddled in conversation and headed your way, you are wise to run.

Job howls in protest at God for allowing such shabby, unwarranted treatment of him. That protest has resounded through the centuries as an epic challenge to all notions of God as we’d like him to be: gentle, just and compassionate beyond measure.

Job is an upstanding sort who pleases God with his kind and wise ways and has been rewarded with a devoted wife, 10 healthy children, thousands of livestock and fine health. Hobnobbing with Satan one day, God points to Job as a prime example of a good man with perfect faith, in whom he is well pleased.

“You can’t be serious! Of course he has faith—he lives on Easy Street!” Satan snorts. (I am using the still obscure Hidas 2014 translation here.)

Satan then suggests a little wager that Job’s faith will buckle under adversity: “We mess with the guy enough and I’ll have him eating out of my hand when he’s not cursing you!”

God breezily consents, tossing Job’s well-being onto the table as his sole bargaining chip with but one proviso: “Do what you want with him, just don’t kill him.”

Satan, overjoyed and licking his lips in anticipation, then unleashes a reign of unprecedented, undeserved terror upon the hapless Job—killing his thousands of livestock and all 10 of his beloved children, then turning his skin into a mass of festering boils upon which maggots feed. As Job lies in the dirt tearing at his wounds, he howls in protest at God for allowing such shabby, unwarranted treatment of him.

That protest has resounded through the centuries as an epic challenge to all notions of God as we’d like him to be: gentle, just and compassionate beyond measure.

***

***

In his plainspoken but poetic 1987 translation, the classicist Stephen Mitchell calls The Book of Job “the great poem of moral outrage. It gives voice to every accusation against God, and its blasphemy is cathartic.” Then he adds: “Job’s vision ought to give a healthy shock to those who believe in a moral God.”

We should recognize here that God has no skin in this game he’s playing with Satan. Many modern theodicies (“theodicy” being the term for rationales of why evil exists) posit a God who often restrains himself for his own inscrutable reasons from intervening directly in human affairs, but who “suffers along with his creation” at every act of evil.

But the only one suffering in this account is Job himself, subjected to untold horrors just so God can show Satan what he’s made of and thus win his wager.

Job lets God hear about it too:

Despair grips me by the neck,

shakes me by the collar of my coat.

You show me that I am clay

and make certain that I am dust.

I cry out, and you do not answer:

I am silent, and you do not care.

You look down at me with hatred

and lash me with all your might.

As Job bewails his fate and continues his litany of near-blasphemous “How could you?” questions to the heavens, God, rather than reaching down with a comforting hand, gives Job the back of his hand with a withering verbal blast that begins:

Who is this whose ignorant words

smear my design with darkness?

Stand up now like a man;

I will question you: please instruct me.

God then ridicules Job and starts in with a long list of all that he has created—starting with the very foundations and measurements of the earth, along with every creature in it, all of which he can control with a flick of his finger.

Underneath it all runs the theme: Where were you, you peon, you nothing, you speck of dirt, when I did all these things? And you are asking me to justify myself?”

Job’s suffering is a stand-in for all the suffering of innocents in human life. The other key actors in this drama are three friends (with the marvelous names of Bildad, Eliphaz, and Zophar) to whom Job calls in his grief, seeking consolation. But all of them instead rebuke him for questioning God and suggest he had to have done many wicked things in secret for God to visit such privation upon him. (With friends like these…)

***

***

In truth, Job is innocent—and besieged with ill fortune anyway. How to explain this?

“I am that I am,” God tells Moses in an earlier Old Testament story. That enigmatic statement takes a slight twist in Job, wherein God essentially explains evil and why good people like Job suffer with:

“It is what it is.”

Meaning: “This is life. I don’t have to explain or justify evil and suffering or anything else to you. Matter of fact, it can’t really be justified. It just is. Call it mystery if you must, but just deal with it.”

Believers in a deity have traditionally “dealt with it” in two ways:

1) by positing a “devil” who actively works to subvert the will of God in our lives and often enough succeeds, and 2) by simply submitting in humility to God’s inscrutable ways, just as Job ultimately bows down at his story’s conclusion and says:

I had heard of you with my ears;

but now my eyes have seen you.

Therefore I will be quiet,

comforted that I am dust.

***

Those positing a benevolent and responsive God are faced with a dilemma on whose horns their entire faith rests in all fear and trembling. They are taught to pray to God for intervention when their children and other loved ones or themselves are ill or abducted or lost in a flood or a war zone, to rejoice when their prayers are “answered” and their loved ones enjoy a reprieve, but then to submit meekly (“Who are you to question me?”) when their prayers are ignored and calamity upends their lives.

This is a most enviable position for God: credited for all good things, unquestioned for all the bad, worshipped through it all by those who “will be quiet, comforted that I am dust.”

And so we are, blown hither and yon by the winds of cruel fate, unanswered in our desperate pleas for some kind of rationale, some response to the question, “Why me, Lord?” and its cousin, “How long, Lord, how long?”

The fact that the answers in The Book of Job are pretty much “Why NOT you?” and “Could be forever” points to God as not so much a “What” as an “Is.” Not as a Being but a Process, not as an Actor but a Context, not as a Noun but a Verb.

God as the “Is-ness” of things, the all-powerful-because-pervasive habitation and context of all that ever has been or will be. Paraphrasing the voice of the divine here, I would simply say:

This is just how things are.

Accept it, don’t question it,

Adapt to it, then leave it be.

Find solace amid your sorrow,

And be glad for whatever joys

Come your way.

Notably, once Job completely accepts his fate and fully absorbs the “Is-ness” of his situation, God ends the action in The Book of Job in fairytale fashion by restoring to him all that was lost—even larger herds, 10 new children, and good health to a ripe old age.

Chastened and all the wiser for how life truly is, Job is newly glad for whatever joys come his way.

***

Joni Mitchell has always been among the most literate of songwriters, but she outdoes herself here in this most remarkable work: “The Sire of Sorrow (Job’s Sad Song)”

***

Rotating banner photos (except books) top of page courtesy of Elizabeth Haslam, some rights reserved under Creative Commons licensing, see more at: https://www.flickr.com/photos/lizhaslam/

Books by Larry Rose, Redlands, Califiornia, all rights reserved. Contact: larry@rosefoto.com

Small storm photo near top of page courtesy of Temari 09, northern California, some rights reserved via Creative Commons licensing, see more at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/34053291@N05/

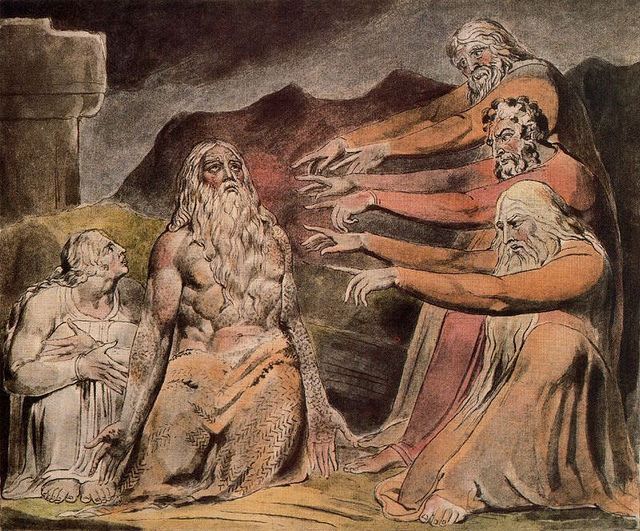

Photos of William Blake’s “Illustrations of the Book of Job” courtesy of the Ergsap Team, a virtual art museum, some rights reserved under Creative Commons licensing, see more at: http://www.flickr.com/photos/ergsap/ and https://www.facebook.com/ErgsArt

Finally, I am well aware of problems related to gender assignations of the divine, and try when possible for gender-neutral references. In the case of this Old Testament tale, however, it felt overly strained and untrue to this specific story’s history to use inclusive language. Besides which, I don’t know that women would much want to claim a God who says, “Too bad!” when her suffering servant reaches out in distress…

Drew – my favorite Mitchell song! Brave and creative in addressing faith’s embarrassment around suffering. I have used the original in worship before. Not sure the male chorus and symphony of this dramatic arrangement help the more sublime and subdued confessional nature of Job however. But maybe closer to Job’s ranting and wasted breath. A tough lesson to carry inside for sure – your comments are very helpful…

andrew: very courageous for you to step into the world of Job, and take us with you. When a 22 year old female in-law family member of mine was murdered in Washington DC in 1967, all sorts of condolences to her parents quoted Job. Job was helpful when life was intensely painful and we felt hopelessly bitter. It is harder to visit Job when things are good in life. But, visiting Job today makes me happy for the wisdom that comes with aging. How sad and empty life can be for those young uns who have not yet visited the depth of life. Thanks for sharing. I love joni mitchell. She is a polio survivor and that has to make one question the goodness of God.

Now that is some post Andrew! I remember first encountering Job as a soph philosophy student in

1967 and realizing for the first time as an adult that for me, the God of the Old Testament is one angry

uptight fella (most of my churching was liberal protestant/young life – major focus on New Testament/Jesus and sort of ignored the Oldies… but loved following your thread and your nuevo-zen like “paraphrasing of the divine…” – accepting what is – tall order sometimes – being a music fan, and a big Joni fan, I had not followed all of her more recent stuff and didn’t know the Sire of Sorrow – wow, did hear her on a long interview on Q (http://www.cbc.ca/player/Shows/Shows/Q+with+Jian+Ghomeshi/Joni+Mitchell/ ) – she has some pretty hard bark on her after all these years, sharp insights, sometimes tough to relate to… found it most captivating however… Thanks for a thought -filled post mate!

Oh, my brother Drew, how timely and important this post is for me. We recently attended a memorial service for a young man from our small town whose younger brother grew up with our daughter. The young man, Wes, was a great kid growing up: kind, humble, sensitive, smart, responsible, and a terrific athlete. He was a role model and friend to the younger kids, including our daughter. News of his death as a healthy, successful twenty-something (he mysteriously died of natural causes in his sleep) devastated us all and had us looking toward the sky asking Job-like questions about how this could possibly be true. After much reflection, grieving, and conversation, the futility of searching for why set in. As one person remarked in her eulogy of Wes; “death is part of life. It’s hard, but it just is.” On another resonant front for me is Gabby Giffords. Her Jan 8 guest piece in the NYT focuses on lessons learned from her extensive re-hab work in PT. Giffords courageously and steadfastly practices the acceptance of is-ness and getting on with life. How could this heinous intrusion to her life have happened to Gabby? And why? She demonstrates to us that the questions are much less important than the acceptance of the circumstance and the determination to keep on keepin on. Many thanks, Drew.