“Everson has been accused of self-dramatization. Justly. All of his poetry…is concerned with the drama of his own self..Everything is larger than life with a terrible beauty and pain. Life isn’t like that to some people and to them these poems will seem too strong a wine. But of course life is like that.”

I love those lines, which come from the introduction to poet William Everson’s 1948 volume, “The Residual Years.” They were written by his friend and fellow poet Kenneth Rexroth, who came up for discussion here a few posts ago, and who served as a kind of mentor to Everson and other younger poets who had gathered around him in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1950s.

Rexroth’s droll insistence that “of course life is like that” points to the fact that even when we try to numb ourselves with various inebriates (including electronics and overwork) or present ourselves externally as even-tempered and even blasé observers of a Self we’re not all that taken by, inside we can be—and often enough are—hot roiling messes, driven by passions only marginally under our control, by events totally beyond our control, and by genes and histories that shape us in ways we spend a lifetime trying to understand.

It is good we have poets and other artists who are willing to carry that load, explore its depths, and proclaim to all those who come across their work: “Life is beautiful and awful and full of devastations and griefs and glory. Welcome to mine.”

***

Give me my pain for purge.

Give me my pain to heal me on,

Lord and Master,

Burn me black and burn me brittle

But slip me deliverance.

***

***

William Everson became a friend of mine for a few years after I wrote a profile on him for the “San Francisco Chronicle” Sunday magazine in late March, 1983. (Camera phone photo of the cover above.) I had visited him in December at his woodsy Santa Cruz home for a long day’s interview and hike that ended with him pulling out a bottle of wine to share.

I subsequently saw him half a dozen times or so over the next several years when he conducted his one-of-a-kind readings around the Bay Area, and we’d occasionally touch base via phone or mail.

Browsing the first few pages, I sunk down into my couch and stayed there for, I don’t know, maybe five years, it was hard to tell…

He was “only” 71 at the time of our interview, and working on a last epic autobiographical poem. But his energy was waning with the tremors and constraints wrought by Parkinson’s disease, and with his long and shaggy white beard, he seemed old as Father Time himself.

“I’m almost ready to die,” he confided to me. “I just can’t find the right poetry to allow it yet.” As it happened, he lived another 11 years but never did complete the epic.

William had come to my attention via my graduate school woman friend, who bought me a volume of his poetry after a hip nun had spoken of him glowingly at the seminary where my friend was studying to become a minister. Browsing the first few pages, I sunk down into my couch and stayed there for, I don’t know, maybe five years, it was hard to tell, before I got my bearings and got on with a life that would be, I felt then and which has turned out to be true, forever altered by the experience.

William (I always called him that, even though his friends of longer standing all called him “Bill”) was a poet of fierce physical presence and even fiercer internal sensibility. Tall, lean and angular at 6’4″, he understood like few other poets the power of personal presence beyond just words on a page.

Despite a somewhat high-pitched voice and a truly gentle and caring spirit, he absolutely commanded a room with the power of his personal presentation. In the years he wasn’t wearing a monk’s habit (more on that below), he would usually don a broad-brimmed hat, bear claw necklace, buckskin jacket and jeans to effect an archetypal man-of-the-deep-woods persona.

At a Berkeley reading I attended in the mid-80s, he came out on stage, proceeded to fix the audience with a withering stare, going west to east, south to north, his Parkinsonian arm clattering against his side for added effect.

Bringing the audience fully into an excruciating silence that probably lasted 45 seconds but seemed like hours, he finally moaned to the heavens, “The agony, the agony…”

“People will not read my poems, but when I read to them I can spellbind,” he had written in his personal journal years earlier.

***

William had grown up in the San Joaquin Valley, the son of Christian Scientist converts. He began his poetic life as a nature poet and pantheist in the mold of his idol Robinson Jeffers, chronicling the unfeeling ferocity and “is-ness” of the natural world and his search for a place in it.

The sky darkens;

Lights of the valley show one by one;

The moon, swollen and raw in its last quarter,

Looks over the edge;

And I kneel in the grass,

In the sere, the autumn-blasted,

And seek in myself the measure of peace

I know is not there.

Over time, he came to correlate his nature-love in a way that Jeffers didn’t: with a highly charged near-worship of human carnality as the closest we will ever come to knowing God.

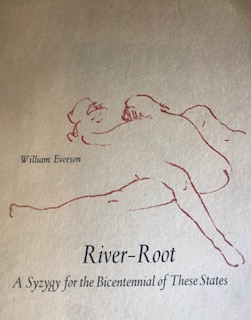

That preoccupation reached its apotheosis with publication of “River-Root,” a 45-page narrative poem depicting a single sexual act that Stanford University professor and critic Albert Gelpi at the time called “the most sustained orgasmic celebration in English, perhaps in all literature.”

Surveying the landscape of glitzy or simply vulgar or debasing treatments of sexuality that prevail today, there would seem to be little or nothing that would refute Gelpi’s claim.

Everson saw the sexual act in prodigious archetypal terms, a rushing river over rocks and untamable rapids, an occasional resting in jetties, then a resumed tumbling like great boulders and mountains and meteors as they quake and collide and split apart before ultimately coming to rest, the underlying impetus of desire for union with God finally achieved.

For over the bed

Spirit hovers, and in their flesh

Spirit exults, and at the tips of their fingers

An angelic rejoicing, and where the phallos

Dips in the woman, in the flow of the woman on the phallos shaft,

The dark God listens.

For the phallos is holy

And holy is the womb; the holy phallos

In the sacred womb. And they melt.

And flowing they merge, the incarnational join

Oned with the Christ. The oneness of each

Ones them with God.

Forty-five pages of that and a whole lot more explicit narration can leave one almost as exhausted as our lovers wind up being on the page, but that was no doubt one of Everson’s purposes in taking sexual union out to the nethermost regions of human ecstasy and actualization.

It also bears mentioning now that 1976 was only the publication date of “River-Root,” which was actually written in 1957. (His signed copy of the volume he later sent as a gift to me is shown at top of this post.)

Everson wrote “River-Root” in the sixth year of what turned out to be an 18-year stint as “Brother Antoninus,” a lay monk of the Dominican Order in the Bay Area who devoted himself to serving the poor, washing dishes and other humble tasks while also writing poetry of sexual ecstasy and epic spiritual torment which he regularly read on poetry platforms around the Bay Area while wearing his monk’s habit.

That is why he was also known at the time as “The Beat Friar,” alluding to his Beat Movement compatriots who rather joyfully flouted all cultural norms. Unlike him, many of them made a virtue of their irreligiosity.

Everson’s trajectory had been very different, his imagination having been captured by a love affair and subsequent marriage in 1948 to returned-to-the-faith Catholic poet Mary Fabilli. It was the second marriage for both.

Accompanying her to midnight Christmas Eve mass later that year, he had what he considered an ecstatic religious experience that compelled him to join Fabilli in her Catholicism. In a cruel twist of fate, his conversion rendered their marriage invalid in the eyes of the church—they had both been divorced.

That set the stage for their disengagement and Everson’s metamorphosis into Brother Antoninus in 1951. But the dramatics of The Beat Friar life were hardly coming to a close.

***

Asked to counsel a troubled 18-year-old woman in 1965, the now 53-year-old Antoninus soon found himself in tumultuous waters again as both parties began feeling an attraction for each other.

Four years of push-and-pull later, Antoninus was at UC Davis reading a poem he had written for the woman, after which he theatrically tore off his monk’s habit and announced to the stunned crowd that he was leaving the order and re-entering secular life as William Everson, poet, and soon-to-be husband to Susanna and step-father to her two-year-old son, whom he later adopted.

It was a typically dramatic gesture for this otherwise gentle soul, and the media ate it up. Nearly a year later, the “Pacific Sun” weekly newspaper in Marin County published the only photographs taken at the event, a sequence of the disrobing that Everson had undertaken on stage. A photo of those photos captured by E David Show is worthy of note, I think, here.

***

***

William and Susanna enjoyed an ostensibly happy marriage for many years at their Santa Cruz home he had dubbed “Kingfisher Flat,” before divorcing in 1992, several years after I had lost touch with him. He died in 1994 at age 81.

Few poets survive on book sales, and after leaving monastic life William taught poetry for 11 years to great acclaim from students at UC Santa Cruz, a satisfying late career that let him influence a new generation and gave him the regular stage that he loved so well.

“I’m happy,” he had told me in our interview. “Never happier in my life. I’ve done a lot of agonizing, the number 1 agonizer of the day. But I’ve won something immensely satisfying to me. Life keeps getting better. Old age is so much more satisfying than youth was that I have utterly no regrets.”

I saw him for the last time in maybe 1988, when he was to do a reading at a church in Berkeley. Driving down from Santa Rosa, mental images were coursing through my mind of the multiple times I had seen him read, always an event, a drama, food for a long night’s reflection.

Entering the church, I espied him on stage, hunched in a wheelchair with his head almost down on his trademark bear claw necklace, being tended to by Susanna. The program began with a moderator offering a few introductory remarks and then explaining that William would offer only brief selections from his poems and then give way to others reading for him.

Wheeled to the front of the dais, William started in, his voice quavering and barely above a whisper, more or less unintelligible. No more withering stare nor anguished claims of agony, but agony itself, writ all the larger for its wholly unmetaphorical reality.

It was a scene of deep pathos, the old fire now gone, rent asunder by illness and the merciless passage of time. After a few minutes of halting words interspersed with silence that retained none of its former compelling power, it was obvious to everyone, including himself, that going on served no good purpose.

I watched as he was wheeled back into place, and as a speaker approached the lectern I decided to leave, knowing it would be the last time I would see William, bidding him a silent adieu as I headed out into the night.

***

In honor of the devout years…

***

Check out this blog’s public page on Facebook for 1-minute snippets of wisdom and other musings from the world’s great thinkers and artists, accompanied by lovely photography.

http://www.facebook.com/TraversingBlog

Deep appreciation to the photographers! Unless otherwise stated, some rights reserved under Creative Commons licensing.

Elizabeth Haslam, whose photos (except for the books) grace the rotating banner at top of page.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/lizhaslam/

Library books photo by Larry Rose, all rights reserved, contact: larry@rosefoto.com

I’m not familiar with William Everson’s poetry, but your description of the reading of his own works had me search through my too extensive and now considered outdated CD library for “Poetry Speaks” , a three-volume CD with readings from Tennyson to Plath and approximately forty in between. No Rexroth or Everson included, but Beat poet Ginsburg and environmentalist Jeffers (an Oxy grad for us Eagle Rockers) do find their way into “Poetry Speaks.” For those who haven’t heard readings from the greatest poets of the late 19th and 20th (Dylan Thomas, T.S. Eliot, W.H. Auden, Langston Hughes, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Elizabeth Bishop et al) centuries, it gives one a new and usually more appreciative respect for their words. As for “River-Root”, a 45-page poem on a sexual orgasm, well…maybe I better leave my comment at that…WELL.

Yeah, Robert, at this point I suspect there is probably a lot more poetry available on You Tube, both audio but with some film as well, than there is on a CD from yesteryear. And the other thing is guys like Rexroth & Everson were usually left out of such collections, given American poetry’s longtime East Coast bias, which Rexroth in particular often railed against.

Everson considered Jeffers his idol & mentor, though he never met him. But coming across a Jeffers poem one day in the library is what turned a light bulb on in Everson’s head, more like a lightning bolt, actually, and he always attributed that moment to his finding his vocation as a poet.

Oh, and just to clarify: “River-Root” is about far more than an orgasm. It was a lonnnnggg encounter, and Everson covered every bit of it, first to last. :-)

He wrote it soon after doing a deep dive into Jung, so the archetypal elements roar right through all of it, in true epic fashion…

What’s a YouTube? Is Jung some woman Everson had a deep dive into? Maybe I better stay away from “River-Root”, the 21st century or even some pathetic attempt at humor!

Hi. I was one of those who called him Bill. Forgive the one-upmanship. He would not have minded if you had, but your motive was honorable in calling him William. I loved him very much and he helped me deeply in many moments of pain, there in the cabin in Kingfisher Flat. I still have preserved my copy of the Chronicle mag that I was amazed to find bundled in with my newspaper one Sunday, when I was living in Oakland.

I kept in touch with him until the day Jude told me he couldn’t come to the phone. Ever.

I went to an Allen Ginsberg reading in Berkeley in ’94 or ’95 and I took the opportunity during the question-and-answer time to ask what Allen Ginsberg thought of Bill. I had no idea what a current of respect and love I was about to unleash. I’ll just paste in this account I wrote of that event:

In 1975, I took William Everson’s course “Birth of a Poet” at UC Santa Cruz. That was to prove to be a vitally-important hinge-point in my life.

Here is the course description for that class:

“A venture in charismatic vocation. Its purpose is to teach, not how to write a poem, but what a poet is. It explores the interior disposition necessary to sustain the witness which any visionary calling entails. For this reason its relevance is not confined to aspiring poets alone, but applies to every role demanding an heroic consciousness. Its aim is wholly interior, and like the resolution of a ritual of the sustaining of an ordeal, its degree of success cannot be measured. Almost certainly its influence will show only in later years. The passing grade indicates that the student has fulfilled the supplementary outside work assigned (the keeping of a dream journal – which I began to do then and have not stopped).”

A few years after that, Bill and I became personal friends. He was my mentor for about 20 years, dating from the first time I dropped into his office hours at UC Santa Cruz, after having taken his class. I told him of my traumatic first day in kindergarten when I was taken aback by the hole the other kids were sliding through on the climbing structure and wanted my mom to help me do that before I went in.

We spoke of the Roman Catholic church, which I was soon to be initiated into due to Bill’s help in getting my mind around the right way. He said the Roman Catholic church today is like a wilted rose; it’s still beautiful, but it is sickly and old. With Bill’s help I was able to navigate around all the hopelessly out-of-it and stale theological interpretations of modern things according to wilted-rose rules.

I remember how benign and fatherly Bill was, to say to me as we were parting, “Before you know it you’ll be sliding down that pole with no hang-ups at all!”

After that I would visit him at his cabin in Kingfisher Flat, where he would counsel me on how to navigate whatever the personal difficulty I was having at the time was. He was the best counselor I have ever had, since he had been steeped in Jungian thought during his seventeen years as a Dominican monk, and due to the 40 or so years of difference in our ages.

As you might well imagine, coping with his death was a difficult hurdle for me, as he had been a real source of wisdom and comfort that I had relied on for some time. What is more, he was a kind of benign father figure… He performed the function for me of what Robert Bly calls the “male mother” – an older man who nurtures and supports the growth of a younger man.

About two years after Bill’s death I attended a poetry reading at the Gaia Bookstore in Berkeley given by Allen Ginsberg.

During the question-and-answer period I steeled my nerves and asked the poet, “I wonder what your estimation of William Everson is, since I have heard that he is considered to have been one of the Beat poets.”

I was amazed at the vigorous and enthusiastic response this drew from Allen, who asked around to see who had heard of Bill. Virtually no one had.

Allen went on to give the people assembled there a quick rundown of Bill’s career as a California poet and his seminal role as one of the founding members of the San Francisco Renaissance. His admiration was obvious, which was very gratifying to me indeed!

He said words to the effect that, “Without the ground-breaking work done by Bill and Kenneth Rexroth here in the Bay Area, we, who were just visitors really, could never have accomplished what we did… He was a kind of father to us at the time.”

I was elated, because the risk I had taken had paid off. In my wildest dreams I wouldn’t have expected that paean as a response to my question. After all, Ginsberg could have just dismissed my question with a curt “Oh yes, I remember him. Much too Catholic for my taste”. But there was no disapproval or dismissal of either Bill or of my question; on the contrary, he seemed pleasantly surprised to be reminded of someone he had held dear.

Sometimes I chide myself for just dropping names to talk to the famous. On the other hand, there was no other way I would ever have been able to find out what Allen Ginsberg’s impression and estimate of Bill was, and that is an important datum in my world-view or sense of the way our culture is unfolding. I am glad I asked that question, because I know something I otherwise wouldn’t know – that Allen Ginsberg, whom many consider the supreme American poet of the latter half of the 20th century, shared my esteem for my friend. Which confirms my sense that Bill Everson is an overlooked diamond in the rough, a secret treasure, and his work may yet blossom.

I like to think that in the course of time, Bill’s fame will increase, as his work is gradually discovered to have timeless value, like that of other artists who were underappreciated in their own lifetimes. I hope, too, that in time Carl Jung’s psychology will gain ascendancy over others whose fame has eclipsed his, being more immediate and sensational. But I am straying from my account, my account of that momentous encounter with the more famous beat poet, Señor Ginsberg…

———

At the time of Ginsberg’s reading I was planning to visit Bill’s grave, which is at the Dominican cemetery in Benicia, for the first time.

When my turn to speak personally with Allen came (having stood in line as others spoke with him and got his autograph, with – to add a somewhat bizarre element to the moment – the hippie clown Wavy Gravy standing behind Allen, presiding silently as one admirer after another had his personal moment with Allen Ginsberg), I told the author of Howl how important Bill had been to me as a friend and mentor, and that I was planning to visit Bill’s grave.

From the face I was looking into, gentle eyes looked inquiringly and compassionately into mine as the poet very sincerely asked me to “Say a prayer for me too when you’re at his graveside.”

Some days later I did go on my pilgrimage to say a final farewell to my friend, and carried out in my own way the task Allen Ginsberg had charged me with.

The synchronistic and in a way amazing (to me, anyway) denouement of this story came only a few weeks later, when I heard that Allen Ginsberg himself had passed away.

I’m so pleased you wrote, Bob, and shared as deeply and expansively as you have. Like all of our relationships with everyone, yours with Bill (!!) had and retains a singularity, precious unto itself and like no one else’s with him, and truly a gift for a lifetime. I “knew” and admired William (!!!) from afar for several years before I got to know him via the article I wrote, so had a “relationship” with him in that sense of having one with all those whom we have read and absorbed deeply. But then to come into physical presence and interaction and followup with that person over the course of years is a whole other step that enriches us beyond measure—especially given how generous he was with his time and spirit. I’m grateful for my own experience of that, as you so resoundingly indicate you are for yourself. Yet one more instance of humbly appreciating our good fortune, yes?

Also: love your anecdote about Ginsberg, whom I had the good sense (not always the case!) to make sure I went to see when he made an appearance at College of Marin and I drove down from Santa Rosa many years ago, tired after a long workday but successfully persisting and overcoming my hesitancy with the question, “If not now, when?” Turned out it was just a year or so before he died, and it was a delightful evening of poetry, embellished with the autoharp, if I remember correctly, that he pulled out about halfway through. He also had a young handsome kid backing him with bongos, I think, about whom Ginsberg made multiple sly, not all that vaguely lecherous references of longing and admiration. A man truly unto himself, Ginsberg was, and I’m happy to report that I can turn my head left from the bed I am atop of as I type and espy my volume of his Collected Poems tucked securely on an upper shelf. (Unsigned, dammit!)

Much appreciate this additional stroll down the avenues of memory with you, Bob. Hope you see fit to check back in here sometime—we frequently speak Poetry!